Practice Essentials

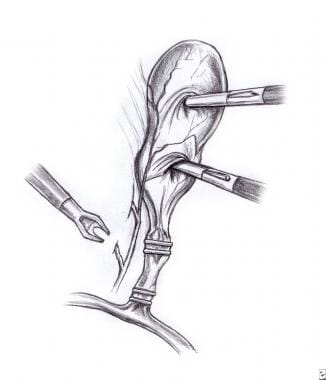

Cholecystitis, which has long been considered an adult disease, is quickly gaining recognition in pediatric practice because of the significant documented increase in nonhemolytic cases over the last 20 years. Gallbladder disease is common throughout the adult population, affecting as many as 25 million Americans and resulting in 500,000-700,000 cholecystectomies per year (see Epidemiology). The image below illustrates the technique for laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Pediatric Cholecystitis. Diagram illustrating the technique for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The gallbladder is retracted with grasping 5-mm laparoscopic instruments, and clips are applied over the cystic duct and artery.

Pediatric Cholecystitis. Diagram illustrating the technique for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The gallbladder is retracted with grasping 5-mm laparoscopic instruments, and clips are applied over the cystic duct and artery.

Although gallbladder disease is much rarer in children, with 1.3 pediatric cases occurring per every 1000 adult cases, pediatric patients undergo 4% of all cholecystectomies. In addition, acalculous cholecystitis, uncommon in adults, is not that unusual in children with cholecystitis. [1]

Because of the increasing incidence of gallstones and the disproportionate need for surgery in the pediatric population, consider cholecystitis and other gallbladder diseases in the differential diagnosis in any pediatric patient with jaundice or abdominal pain in the right upper quadrant, particularly if the child has a history of hemolysis (see Presentation).

Cholelithiasis is the most common cause of acute or chronic cholecystitis in adults and children (see Etiology).

Abdominal ultrasonography has become the diagnostic tool of choice in evaluating cholelithiasis, although it is less accurate in cholecystitis (see Workup).

Cholecystectomy is the standard of care for cholecystitis. Medical treatment is used in patients who are not candidates for surgery, as well as in certain other settings (see Treatment).

Background

Cholecystitis is defined as inflammation of the gallbladder and is traditionally divided into acute and chronic subtypes. These subtypes are considered to be two separate disease states; however, evidence suggests that the two conditions are closely related, especially in the pediatric population.

Most gallbladders that are removed for acute cholecystitis show evidence of chronic inflammation, supporting the concept that acute cholecystitis may actually be an exacerbation of chronic distension and tissue damage. Cholecystitis may also be considered calculous or acalculous, but the inflammatory process remains the same.

Types of gallstones

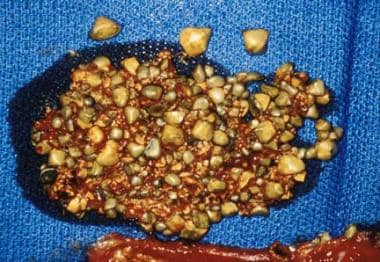

Three major types of gallstones may form in cholelithiasis: cholesterol, pigment, or brown. However, most gallstones have components of more than one type.

Cholesterol gallstones (shown below) are radiolucent and are composed of cholesterol (>50%), calcium salts, and glycoproteins. They form within the gallbladder and migrate to the bile duct.

Pigment gallstones are black, often radiopaque, and are usually associated with hemolytic diseases. Radiopacity and color are related to an increased concentration of calcium bilirubinate, which interacts with mucin glycoproteins to form gallstones. These gallstones also form within the gallbladder and migrate to the ductal system.

Brown gallstones, in contrast, form within the ductal system and are orange, soft, and greasy. They are composed of calcium salts of bilirubin, stearic acid, lecithin, and palmitic acid. These gallstones are more often associated with infection. [2]

Go to Cholecystitis and Acalculous Cholecystitis for more complete information on these topics.

Pathophysiology

Distinct complications can occur at any point in the course or treatment of gallbladder disease. They can be divided into complications of gallstones, inflammation, and treatment. At any of the three stages, disease may exacerbate preexisting medical conditions, leading to cardiac, hepatic, pulmonary, or renal demise.

Gallstones may cause obstruction of the common bile duct, acute or chronic cholecystitis, cholangitis, gallbladder perforation, or pancreatitis. Choledocholithiasis occurs less often in children. Risk increases with age. Nevertheless, obstruction of the common bile duct may still accompany pediatric cholelithiasis, especially in the presence of congenital ductal narrowing or stenosis, and it may cause hepatocyte damage. Rule out common bile duct stones in the presence of any jaundice.

Stones may also perforate the gallbladder, allowing bile leakage into the peritoneum, or create a cystoenteric fistula, possibly leading to a gallstone ileus.

The most common complication of gallstones in children is pancreatitis, reported to occur in 8% of cases. The course is usually mild and resolves spontaneously with passage of the stone, which occurs in several days.

Acute infection and inflammation of the gallbladder or ductal system may lead to sepsis or local spread of disease. Perforation, abscess, empyema, infarction, or gangrene may develop in acute cholecystitis, causing peritonitis and threatening the patient's life. Chronic cholecystitis may lead to acute hydrops, acute cholecystitis, or, more insidiously, porcelain gallbladder.

The well-known radiographic finding of porcelain gallbladder is caused by chronic calcium deposition in the wall of the gallbladder as a result of inflammation. Although early studies reported a 12-60% incidence of carcinoma arising in the gallbladder wall of patients with porcelain gallbladder, more recent data suggest that the cancer risk is significantly lower (approximately 7% in one large series). [3]

Etiology

Chronic cholecystitis

Chronic cholecystitis is most often related to gallstone disease but has been documented without gallstones. Its course may be insidious or involve several acute episodes of obstruction. The initiating factor is thought to be the supersaturation of bile, often with cholesterol crystals and/or calcium bilirubinate, which contributes to stone formation and inflammation.

These processes lead to chronic obstruction, decreased contractile function, and biliary stasis, which contribute to further inflammation of the gallbladder wall. Biliary stasis also permits the increased growth of bacteria, usually Escherichia coli and enterococci, which may irritate the mucosa and increase inflammatory response.

Chronic acalculous cholecystitis is less understood, but it may result from a functional deficiency of the gallbladder, which leads to spasm and an inability to appropriately empty the gallbladder contents, causing chronic bile stasis.

Acute cholecystitis

Acute calculous cholecystitis results from a more sudden obstruction of the cystic duct by gallstones, which causes distension of the sac, edema, and bile stasis with bacterial overgrowth. These events lead to inflammation and a local release of lysolecithins, which further exacerbates the inflammatory process. In addition, edema of the wall and duct reinforces obstruction and may cause ischemia of the local tissue, with the release of still more inflammatory mediators.

Local lymph node hypertrophy and duct torsion or congenital anomalies may further complicate the obstructive process. As obstruction and inflammatory tissue damage progress, bacteria may proliferate. Bile cultures are positive in 75% of cases, usually with E coli, enterococci, or Klebsiella species. Bacterial infection most likely follows tissue damage, but after colonization, the severity of the disease can dramatically worsen. This cascade of events quickly leads to pain and, possibly, a toxic appearance.

Acute acalculous cholecystitis develops in a similar manner but from different etiologic factors than acute calculous cholecystitis does. Acute acalculous cholecystitis is most often associated with systemic illness, whether chronic or critical and acute. Increased mucus production, dehydration, and increased pigment load all increase cholesterol saturation and biliary stasis, whereas hyperalimentation, assisted ventilation, intravenous narcotics, ileus, and prolonged fasting contribute to cholestatic hypofunction.

These conditions allow the formation of biliary sludge and may lead to obstruction. The resulting inflammation and edema lead to compromised blood flow and bacterial infection, as in acute calculous cholecystitis; however, the compromised blood flow appears more central in acute acalculous cholecystitis because acute acalculous cholecystitis can occur in vasculitides (eg, Kawasaki disease, periarteritis nodosa), presumably because of direct vascular compromise.

Common causes of gallstones

All gallstones require similar conditions to form. First, the bile must be supersaturated either by cholesterol or by bilirubin. Second, chemical kinetics must favor nucleation of cholesterol. This occurs when cholesterol is no longer soluble in bile. Finally, stasis of the gallbladder allows cholesterol or calcium bilirubinate crystals to remain long enough to aggregate to form gallstones.

Many disease processes can precipitate or foster these events. Infection induces the deconjugation of bilirubin glucuronide, thereby increasing the concentration of unconjugated bilirubin in the bile. Hemolysis overwhelms the conjugation abilities of the liver, increasing the amount of unconjugated bilirubin in the bile. Hemolytic diseases include hereditary spherocytosis, sickle cell disease, thalassemia major, hemoglobin C disease, and possibly uncontrolled glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G-6-PD) deficiency.

Multiple blood transfusions also increase the pigment load. This predisposes the bile to the formation of biliary sludge.

Dehydration concentrates the bile, thereby increasing viscosity and stone formation. Cystic fibrosis (CF) is associated with increased mucus production and may cause a similar scenario.

In rural Asia, infections with Clonorchis sinensis (also called Opisthorchis sinensis) or Ascaris lumbricoides are predisposing conditions for brown gallstones. In the United States, these gallstones are more rare, although they have been found after cholecystectomy in which the bile was infected (most often by E coli) and in infants and children infected with Staphylococcus, Enterobacter, Citrobacter, and Salmonella species.

Chronic urinary tract infections may also predispose individuals to the formation of brown gallstones. Isolated gallstones associated with Ascaris have been recorded in the United States. [4]

Unusual causes of gallstones

Gallstones may also be caused by medications. Octreotide, ceftriaxone, [5] cyclosporine, [6] and furosemide [7] have all been associated with gallstone disease. Ceftriaxone causes a reversible pseudolithiasis through several mechanisms. Ceftriaxone displaces bilirubin on albumin, thereby increasing the blood concentration of unconjugated bilirubin. Ceftriaxone is also secreted in bile, and calcium salts of ceftriaxone have been found in biliary sludge.

Cyclosporine may be lithogenic, but it seems to require high drug levels and hepatotoxicity. Furosemide has also been implicated in gallbladder disease, but it usually is only a compounding factor in the presence of prematurity, sepsis, or small-bowel disease.

Finally, ileal disease or resection has been correlated with cholelithiasis in adults and children, although the risks associated with resection seem to be highest after puberty. [8] These patients have an increased cholesterol secretion and a lowered bile acid secretion, which leads to cholesterol supersaturation.

Acalculous cholecystitis

The aforementioned diseases may also contribute to the development of acalculous cholecystitis, because the formation of gallstones is not necessary for the obstruction of the bile duct. In addition, acalculous cholecystitis has been heavily associated with local inflammation, endocarditis, vasculitides, and systemic infection.

Implicated infections include those occurring in typhoid fever, scarlet fever, measles, and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), as well as infections caused by Mycoplasma, Streptococcus (groups A and B), and gram-negative organisms, such as Shigella and E coli.

Acalculous cholecystitis may also occur postoperatively. Tsakayannis et al observed acute cholecystitis occurring after open-heart surgery in four of their patients, although it is more commonly observed in other nonbiliary surgeries and trauma. [9]

Shock, sepsis, hyperalimentation, prolonged fasting, intravenous narcotics, and multiple transfusions are common risk factors for the development of acute acalculous cholecystitis. The presence of four or more of these risk factors has been associated with a strong predisposition to the disorder.

Risk factors for cholelithiasis

Cholelithiasis in infancy is most often related to acute and chronic illness and hyperalimentation. [10] More specifically, risk factors include abdominal surgery, sepsis, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, hemolytic disease, malabsorption, necrotizing enterocolitis, and hepatobiliary disease. Other factors implicated include CF, polycythemia, phototherapy, and distal ileal resection.

The immature hepatobiliary system of infants may predispose them to stone formation. Decreased hepatobiliary flow and immature bilirubin conjugation contribute to stasis and sludge formation. Interestingly, as much as one half of infantile gallstones, especially those associated with hyperalimentation, may resolve spontaneously.

In a review of 693 cases of pediatric cholelithiasis by Friesen et al, infants with the disease tended to be ill and receiving hyperalimentation, and had prematurity, congenital anomalies, and necrotizing enterocolitis as compounding risk factors. [11]

Risk factors for cholelithiasis in children include hepatobiliary disease, abdominal surgery, artificial heart valves, and malabsorption. Gallstones usually contain a mixture of calcium bilirubinate and cholesterol. Hemolysis and prolonged hyperalimentation are significant influences in this age group. (In the Friesen study, hemolysis was the most common underlying condition for cholelithiasis in children aged 1-5 years).

In adolescents, risk factors for cholelithiasis include pregnancy, hemolytic disease, obesity, abdominal surgery, hepatobiliary disease, hyperalimentation, malabsorption, dehydration, and the use of birth control pills.

In addition, early menarche has been shown to significantly increase the incidence of cholecystitis, perhaps because of the lithogenic effect of estrogen on bile. Racial and genetic influences in the adolescent age group are similar to those in adults (see Epidemiology).

Epidemiology

United States statistics

The exact frequency of acute and chronic cholecystitis in children is not known. The overall incidence appears to have increased in the last 3 decades because of the high consumption of fatty foods by young children (ie, Western diet). In children with chronic hemolysis (eg, hemolytic anemias), the incidence of cholecystitis is much higher than in the general population. Biliary sludge and/or gallstones are likely to form in 1 in 5 children with hemolytic anemia before their adolescent years.

Sex distribution for cholecystitis

In adolescence, differences in the frequency of cholecystitis based on race, genetics, and sex become more evident. Adolescent girls are much more at risk of developing the disease than boys are. The female-to-male ratio in white adults is 4:1; in adolescents, the ratio is estimated to be 14-22:1.

Prevalence of cholecystitis by race and ethnicity

Racial and genetic influences in the adolescent age group are similar to those of adults. African Americans (without hemolytic disease) and the African Masai are less prone to cholelithiasis, whereas Chilean women, Pimas, [12] and whites are more predisposed to this disease.

Two contributing diseases in particular have a genetic component and racial distribution. Hemolytic diseases, including sickle cell disease and hemoglobin C disease, occur almost exclusively in the black population, although thalassemia also has a Mediterranean distribution. Cystic fibrosis, which occurs mainly in whites, may also contribute to the formation of biliary sludge and, possibly, acalculous cholecystitis.

Age distribution for cholecystitis

In the previously mentioned Friesen review of 693 cases of pediatric cholelithiasis, 10% of gallstones were found in children younger than age 6 months, 21% were found in children aged 6 months to 10 years, and 69% were found in persons aged 11-21 years. [11]

Prognosis

Isolated cholecystitis generally has an excellent prognosis if diagnosed and treated appropriately. Children can be expected to return to presurgical functioning soon after cholecystectomy, especially after a laparoscopic procedure. The greatest indicator for poor prognosis is the underlying disease process itself. Cholecystitis that is treated is usually well tolerated.

Children can be expected to do well, although comorbid conditions are common and may cause complications. Risk factors for morbidity and mortality in the pediatric population include associated conditions, such as cystic fibrosis (CF), obesity, hepatic disease, diabetes mellitus, sickle cell disease, and immunocompromise.

Complications that may influence prognosis

General complications, such as pulmonary, cardiac, thromboembolic, hepatic, and renal insufficiency, account for most deaths. Procedure-related complications mainly contribute to morbidity and occur with higher frequency in acute cholecystitis in which symptoms of gallstone disease have been present longer than 1 year. Procedure-related complications are predictable and include hemorrhage, bile duct injury, ileus, pancreatitis, and leakage from the newly created stump. Risks from anesthesia are also noted. In addition, wound infections, abscess, or cholangitis may complicate the postoperative course.

Mortality rates for calculous and acalculous cholecystitis

Most of the data on morbidity and mortality in gallstone disease is derived from the adult population, although some trends can be extracted and applied to the pediatric population. In general, the mortality rate of cholecystectomy in acute cholecystitis has dropped from 6.6% in 1930 to 1.8% in 1950 to nearly 0% in later studies. In one study, the overall mortality rate in 42,000 patients undergoing open cholecystectomy was 0.17%; the mortality rate in patients younger than 65 years was 0.03%.

Acalculous cholecystitis has its own statistics for mortality and morbidity. Mortality in the adult population has been reported to be as high as 10%, and in patients with critical illness, the mortality rate can reportedly reach 50%. The mortality rate in patients with critical illness is most likely related to the close association with severe systemic illness. Concomitant illness and risk factors should be considered when predicting morbidity and mortality in children.

Patient Education

Patient education can be focused on prevention, observation, timely treatment, and information about the intraoperative procedure. Preventive measures include diet and weight management. In addition, educate patients with CF about compliance with pancreatic enzyme and bile acid supplementation.

At-risk patients, whether because of chronic disease of cultural and/or genetic risk factors, should be aware of signs and symptoms of cholecystitis and gallstone disease. This enables them to seek timely medical attention and avoid complications of acute cholecystitis. Finally, educate all patients undergoing operative procedures about preoperative and postoperative care and the expectations and risks of surgery.

For patient education information, see the Digestive Disorders Center and Cholesterol Center, as well as Gallstones.

-

Pediatric Cholecystitis. Diagram illustrating the technique for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The gallbladder is retracted with grasping 5-mm laparoscopic instruments, and clips are applied over the cystic duct and artery.

-

Pediatric Cholecystitis. Photograph of a gallbladder filled with numerous small cholesterol stones.

-

Pediatric Cholecystitis. Operative photograph illustrating the position of small (5 mm, 10 mm) trocars in the abdomen of a 12-year-old child undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. By using this technique, the surgeon can avoid large incisions and remove the gallbladder safely.

-

Pediatric Cholecystitis. Photograph illustrating the role of endoscopic retrieval of common bile duct stones. The picture shows a balloon placed via the endoscope into the ampulla for extraction of a cholesterol stone that was occluding the common bile duct.

Tables

What would you like to print?

- Overview

- Presentation

- DDx

- Workup

- Approach Considerations

- Laboratory Studies

- Plain Abdominal Radiography

- Abdominal Ultrasonography

- Oral Cystography

- Biliary Scintography

- Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography

- Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography

- Endoscopic Ultrasonography

- Cholecystokinin Stimulation

- Histologic Findings

- Show All

- Treatment

- Guidelines

- Medication

- Media Gallery

- References